Project and write-up by Kevin Chen, Maya Shen, Kayo Yin and Kenneth Zheng (in alphabetical order). Blog post adapted from the write-up.

Introduction

In this project, we visualize songs using images that pulsate and move along with the music using Compositional Pattern Producing Networks (CPPN). In addition, the images we use are recognizable or reminiscent of the songs themselves to help viewers feel a connection with the music and gain a deeper appreciation for it.

This project was done for the Art and Machine Learning course offered at Carnegie Mellon University in Spring 2022. This blog post accompanies the Colab notebook here which contains the pipeline to generate visualizations using NeuroMV.

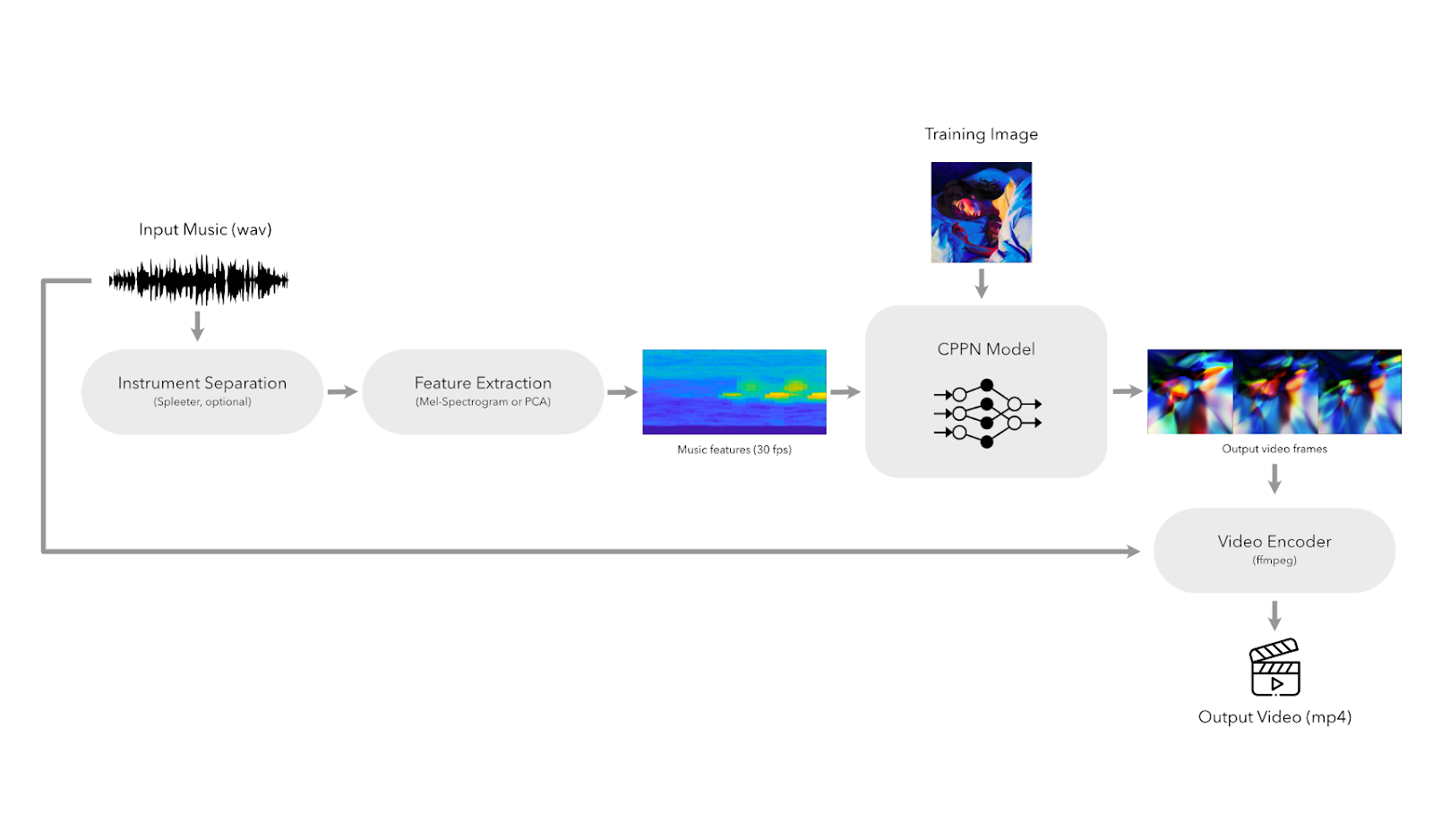

The above figure illustrates the NeuroMV pipeline. In this blog post, we will walk through each step of the pipeline.

Instrument Separation

First, we can optionally separate the instruments in the input audio, to create visualizations for each separate instrument. To do so, we use a source separation model from Spleeter. After separating, for example, the voice from the accompaniment, we can feed the voice audio file and the accompaniment audio file individually into NeuroMV to obtain two separate visualizations. The different visualizations can be recombined to be played side-by-side with the original audio.

Feature Extraction

After obtaining the desired input audio file, we perform feature extraction to obtain a latent vector representation $z$ of the musical features at each timestep corresponding to a video frame at a rate of 30 fps. To do this, we use a Mel spectrogram with a hop size of 1/30th of a second and a window size of double that (1/15th of a second).

A spectrogram allows us to get the energy at various frequency bins at each timestep, which is a good representation of how we hear music. Instead of a traditional (linear) spectrogram, we use one that scales the frequency bins to the Mel scale, which better corresponds to human perception. By changing the number of Mel filters, we are also able to effectively control the size of the latent vector $z$.

CPPN Model

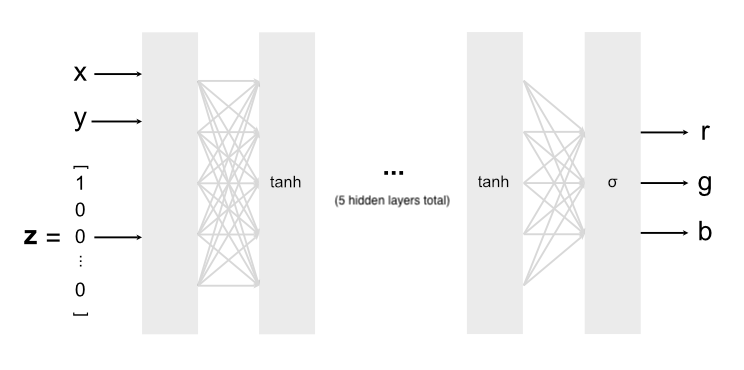

To generate each frame of the music visualization, we use Compositional Pattern Producing Networks (CPPN). Essentially, a CPPN models a given image by approximating it as a mapping between pixel positions $(x,y)$ to pixel colors $(r,g,b)$. Once this mapping has been found, the CPPN model can easily scale and stretch around the image by adjusting the input.

Following previous work using CPPNs to generate abstract art, we use a neural network with $5$ hidden layers as our image generation model, using tanh activations for the hidden layers (which produce a painterly style with soft edges in the generated images), and a sigmoid activation in the final layer to clamp the RGB output values between $0$ and $1$.

CPPN model architecture

In addition to the $(x,y)$ coordinates, we feed a latent vector $z$ encoding music features to the CPPN for each frame, inspired by this blog post. Because the CPPN is a continuous function, if we modify $z$ by only a small amount, the output video frame also varies only slightly, whereas a large modification of $z$ leads to a large change in the output frame. Thus, the variations in music encoded in $z$, both in pitch and amplitude, can be reflected in the output video through variations in the video frames.

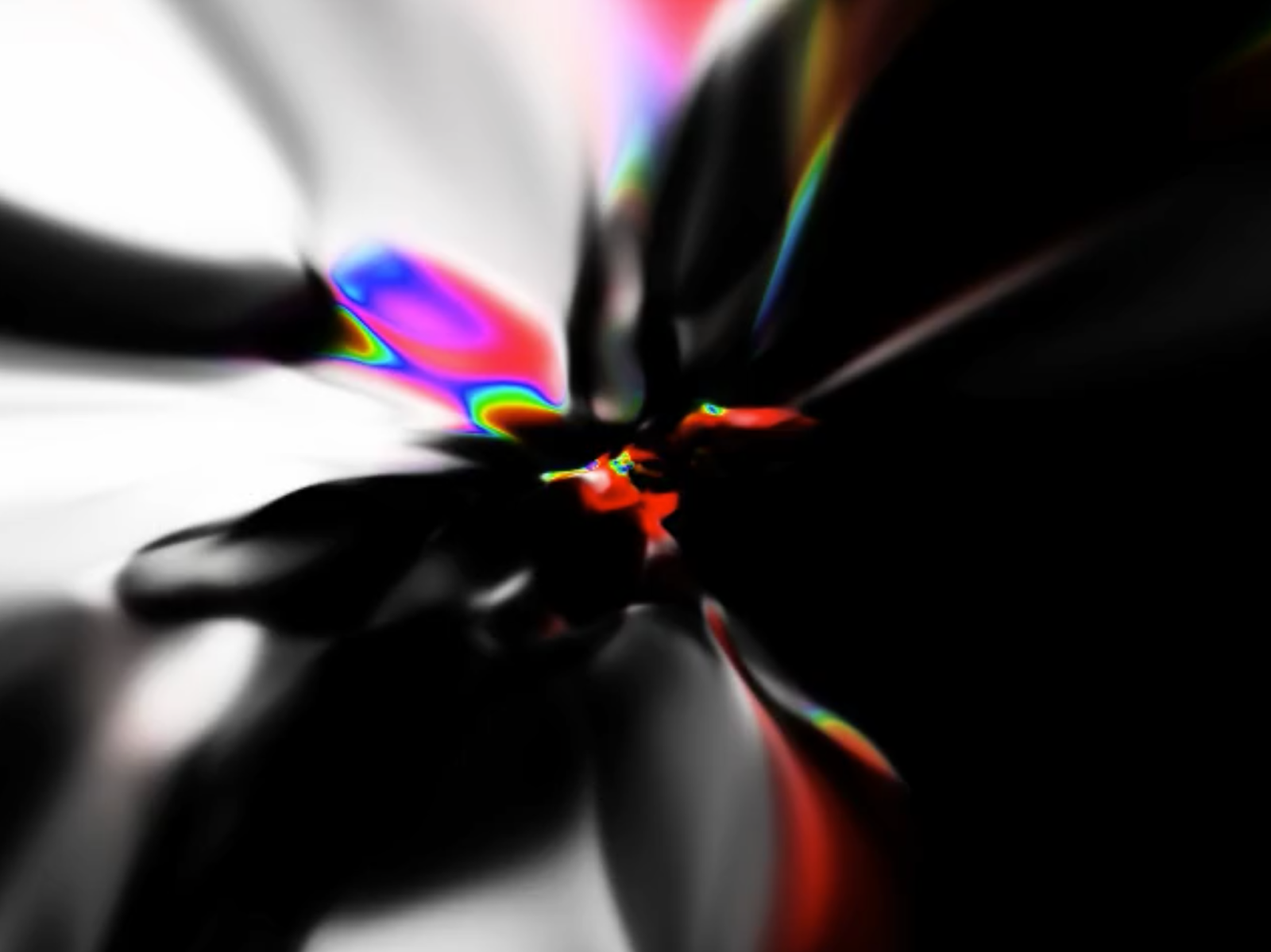

By simply initializing all layer weights randomly from a standard Gaussian distribution, our CPPN model can already generate very interesting abstract images. For example, below is the first frame from a test visualization we did with a randomly initialized CPPN with the song Spectrum by Zedd (full video here).

An example of a frame generated using a randomly initialized CPPN

Pre-training with Images

To add an element of customizability to our music visualizer, we can pre-train the CPPN model to match a reference image. This can be achieved by simply converting a given image to a training dataset, where the inputs are the $(x,y)$ position of each pixel in the image and the labels are their $(r,g,b)$ pixel values. While the model will not be able to perfectly capture all the small details in a training image, it is able to capture the general shapes and colors present, which can influence the look and feel of the resulting visualization.

Below is an example of a visualization frame generated with this method, using the song Liability by Lorde as the music track, and the album cover art of its album Melodrama as the training image. You can see the full visualization for this example here.

Left: reference image (album cover of Lorde’s Melodrama), right: image generated by corresponding trained CPPN.

We tried using the album cover as a default image for various songs we tested, but also experimented with other methods to retrieve reference images including using ML systems like DALL-E or WOMBO to generate images from lyrics/text descriptions, or simply manually choosing an aesthetic or thematic image.

Generating the Video

Finally, we use FFmpeg to combine the generated video frames into a single video, and add the accompanying audio to the video. If we generated multiple videos for different instruments, we also use FFmpeg to combine the videos side-by-side.

Conclusion and Future Work

Overall, we’re very happy with how well CPPN models with Mel spectrograms as a latent representation of music can create visualizations of songs! We are excited to see album covers and other visual representations of our favorite songs move and pulse with the music. By including aspects of songs which aren’t necessarily auditory (e.g. album cover, movie still for a soundtrack) in our visualizations, we hope to bring in novel aspects which may also allow the viewer to have a deeper experience.

In the future, it would be interesting if the images themselves can encode other aspects of songs: for example, generating a sequence of images using text-to-image models by feeding in the lyrics, or generate images guided by the audio by using models such as AudioCLIP.

Images generated using Dream by WOMBO for “Long Lost” by Lord Huron, “Liability” by Lorde, “Electra Heart” by MARINA, and “Formula” by Labrinth based on song title, artist name, and album cover.

Another limitation of our current pipeline is that there is a trade-off between how well the CPPN model reproduces the reference image, and how much variations conditioned on the audio in the video frames we can observe: the longer we train CPPN on the reference image, the more accurate the output image becomes, but the resulting video may become static. Therefore, it would be useful to explore how we can increase the CPPN output accuracy while preserving its sensitivity to the latent music representation.